Lambda calculus typer from scratch - Part 1

NOTE

Prerequisites: You need to be familiar with basic Haskell syntax and understand recursion and higher-order functions. For example, you should be able to implement functions like zipWith and map yourself.

Corresponding code: https://github.com/xiaoshihou514/xingli

Introduction

In the world of functional programming, Lambda calculus is one of the fundamentals. This seemingly simple mathematical system—with just three rules for variables, function abstraction, and function application—is Turing complete, forming the bedrock for functional programming.

When you write an anonymous function like \x -> x + 1 in Haskell, or (x: Int) => x + 1 in Scala, you are essentially using modern variants of lambda expressions. These "function values" treat functions as first-class citizens, allowing them to be passed around and composed like ordinary values.

But why should we care about type inference?

In Haskell, when you write map (\x -> x + 1), the compiler can automatically deduce that the entire expression's type [Int] -> [Int], without requiring you to explicitly annotate the type of every intermediate result. Behind this "magic" lies a type inference algorithm based on lambda expressions.

Understanding type inference enables you to:

- 🎯 Gain deeper insight into Haskell's type system: No longer be puzzled by type error messages

- 💡 Develop type-oriented thinking: Truly understand types and make them work for you

- 🧠 Grasp modern language design principles: The type systems of languages like TypeScript and Rust are all inspired by these theories

Next, we will implement a complete type inference algorithm step by step, allowing you to personally experience the inner workings behind Haskell's compiler.

Basic Definitions

First, let's define Lambda terms and types.

Lambda Terms

Let's start with a few examples:

x(a variable)\x.x(the identity functionid)\x.\y.x(a function that always returns the first argument,left)(\x.\y.x) (\x.x) = left id

The syntax of Lambda expressions is recursively defined by the following three rules:

Lambda terms have the following recursive definition (TL;DR):

- Variable:

x,y,z... - Abstraction:

\x.M, whereMis a Lambda term (equivalent to an anonymous function in Haskell) - Application:

M N, whereMandNare Lambda terms (equivalent to a function call)

Types

Examples: A, A -> B, (A -> B) -> C, (A -> B) -> A -> B

Here we use the simplest Curry type system, meaning: either a base type (Int, String, etc. We will use A, B), or an arrow type Type -> Type (same as Haskell types).

Representation in Haskell

data Term = V Char -- Variable, e.g., 'x'

| Ab Char Term -- Abstraction, e.g., \x.M

| Ap Term Term -- Application, e.g., M N

deriving (Eq, Show)

data CurryType = Phi Char -- Base type, e.g., A, B

| Arrow CurryType CurryType -- Function type, e.g., A -> B

deriving (Show, Eq)

-- For convenience, let's define an infix operator for Arrow

(-->) :: CurryType -> CurryType -> CurryType

(-->) = ArrowWe want to be able to infer that the type of \x.x is A -> A, and the type of \f.\g.\x.f (g x) is (B -> C) -> (A -> B) -> A -> C, etc.

TIP

💡 Give it a try: Can you write a function in Haskell to verify if a type is correct? This is much simpler than inferring the type!

What to do: Type Signature

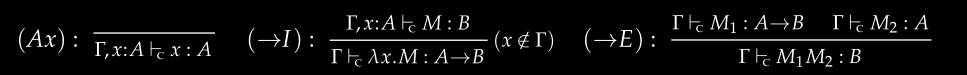

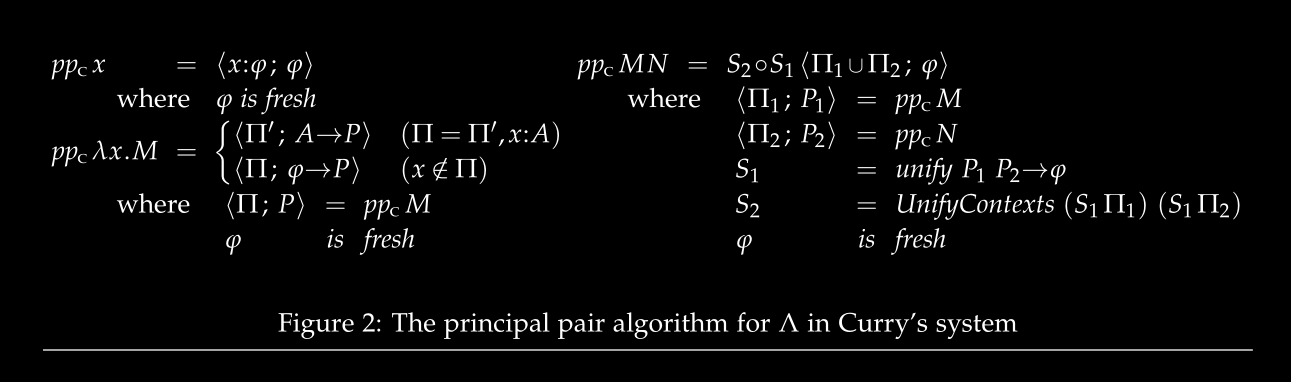

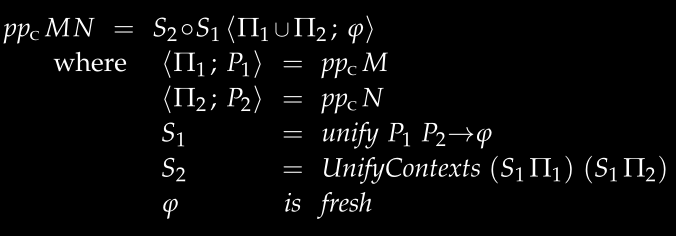

We will implement a type inference algorithm called the Principal Pair Algorithm. It is defined as follows:

If you already understand this, then congratulations, probably no need to read further (

But most people are confused the first time they see it. No worries, let's go step by step.

Understanding the Input and Output

The algorithm returns a tuple containing a context and the inferred type. The context is a mapping that records the type of each variable, which we can represent using Haskell's Data.Map.

Since the algorithm needs to continuously generate new type variables (like A, B, C...), we need to maintain a state to record which letter is currently being used. For simplicity, we assume the letters A to Z are sufficient.

data TypeCtx = TypeCtx

{ env :: Map Char CurryType,

label :: Label

}Define the principal pair (the algorithm's return result):

type PrincipalPair = (TypeCtx, CurryType)Okay, now we can write the type signature for the algorithm:

emptyEnv :: TypeCtx

emptyEnv = TypeCtx Map.empty 'A'

pp :: Term -> PrincipalPair

-- Because we can't magically generate new type names like in the definition

-- we have to maintain this state and pass it around.

pp = pp' emptyEnv

where

pp' :: TypeCtx -> Term -> PrincipalPair

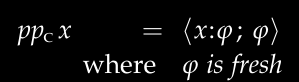

pp' = undefined -- To be implementedCase 1: Variable

Implement the case where the term is a variable:

The formula says: For any variable x, infer a type a (any new type name), and record in the context that x maps to a.

pp' ctx (V c) =

-- record that "A" has bee used, next available letter is "B"

let (a, ctx') = next ctx

-- record type of c is "A"

in (add c a ctx', a)Here, the next function is responsible for generating a new type name, and the add function is responsible for adding a new variable-type mapping to the context.

fresh :: Label -> Label

fresh = chr . (+ 1) . ord

next :: TypeCtx -> (CurryType, TypeCtx)

next (TypeCtx env l) = let l' = fresh l in (Phi l, TypeCtx env l')

add :: Char -> CurryType -> TypeCtx CurryType -> TypeCtx CurryType

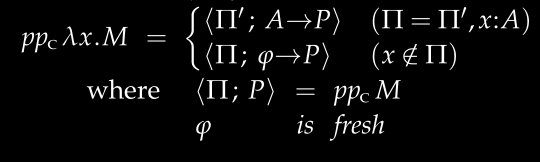

add c ty (TypeCtx env l) = TypeCtx (Map.insert c ty env) lCase 2: Abstraction

This rule handles Lambda abstraction \x.M:

- First, infer the type

PforM - Check if the context already knows the type of

x:- If known (e.g.,

xmust beInt -> Int), then the type of the whole expression isx's type -> P - If not known, assign a new type

atox, then the type of the whole expression isa -> P

- If known (e.g.,

pp' ctx (Ab x m) =

let (ctx', p) = pp' ctx m -- First infer the type of M

in case Map.lookup x (env ctx') of

Just ty -> (ctx', ty --> p) -- If the type of x is known

Nothing ->

let (a, ctx'') = next ctx' -- Otherwise, create a new type

in (add x a ctx'', a --> p)Case 3: Application

Implement the case where the term is an application:

This is the most complex case, handling function application M N:

- Infer the types of

MandNseparately - For the application to be valid, the type of

Mmust betypeof N -> a(a fresh type) - However, the types we assigned to variables earlier were arbitrary, so we might need to unify these types

For example: Inferring the type of f x, pp gives type A for f and type B for x. At this point, we need to unify this function to find a substitution (replacing A with a type that fits the context) such that after substitution, the types suggests that M can be indeed applied to N. This substitution needs to modify all known types in the context (UnifyContext).

Another example, perhaps (\x.x) y:

- Inferring

\x.xyieldsctx1 = {x:A}, typeA -> A - Inferring

yyieldsctx2 = {y:B}, typeB

If one simply merges ctx1 and ctx2:

- This might result in conflicting types (incorrect!)

- Lose data (some vars might be of different types in the 2 contexts)

The right thing to do: don't merge as is, unify the types to make the two contexts consistent.

This part is quite complex, and we will explain it in detail in the next article.

pp' ctx (Ap m n) = s2 . s1 $ (ctx1 `union` ctx3, a)

where

(ctx1, p1) = pp' ctx m

(ctx2, p2) = pp' ctx1 n

(a, ctx3) = next ctx2

s1 = unify p1 (p2 --> a)

s2 = unifyctx (s1 ctx1) (s1 ctx3)

unify :: CurryType -> CurryType -> (CurryType -> CurryType)

unifyctx :: TypeCtx -> TypeCtx -> (CurryType -> CurryType)To be continued...

Give it a shot

Q1 Given Lambda terms:\x.\y.x

- Write out the call chain leading to the final result

- How does the context change during inference? Write out what the context is in each call step

Q2 When inferring the type for \a.a, say initially the context contain Label = 'A':

- What type labels would be produced?

- What's the

Labelin the finalTypeCtx

Q3 Infer the types of the following Lambda terms by hand:

\x.x(id)\x.\y.x(K combinator)\x.\y.y(right)